Share:

Abstract

This paper aims to study the effects of microlens array (MLA) and diffractive optical element (DOE) on skin after 1064nm picosecond laser high-energy irradiation through intradermal laser-induced optical breakdown (LIOB) The radiation of MLA and DOE was tested on dimming paper, tissue model and dark pig skin, and the distribution of microbeams, microbubbles and laser-induced cavitation in the skin was quantitatively compared. Compared with MLA, DOE The microbeams generated on the paper were more uniformly distributed and laser-induced microbubbles were also generated in the model. In vitro skin experiments confirmed that DOE-assisted irradiation had a higher degree of uniformity on the tissue surface compared with MLA-assisted irradiation (deviation of ~26% and ~163 μm). The generated microbeams were more uniform (deviation was ≤3%), and a high density of laser-induced small cavitation bubbles (~78 μm) were found in the dermis. After intradermal LIOB, DOE-assisted picosecond laser irradiation can form subbasal membrane cavitation bubbles. Deep and uniform cavitation for effective skin grading treatment.

Introduction

Melasma is a pigmentary disease that occurs mainly on the face in brown or gray patches. There are many factors that cause pigmentary skin diseases, including genetics, pregnancy, hormonal dysfunction, and ultraviolet (UV) light. But The pathogenesis of melasma is not yet fully understood. Melasma occurs in all populations, but is more common in Fitzpatrick skin types IV to VI because Fitzpatrick skin types contain more pigment phenotypes than other skin types. Treatments for melasma include surgery, medication, radiofrequency and laser therapy. Among the various treatments, high-power laser has become a physical method for breaking up skin pigments due to its advantages of being non-invasive, fast treatment and short recovery period. Popular means of treating melasma. Therefore, a Q-switched nanosecond laser system with multiple wavelengths (532, 755 and 1064 nm) and pulse durations (10-100ns) has been developed and clinically tested to maximize the therapeutic effect of melasma. . However, nanosecond pulse durations are usually longer than the thermal relaxation time of melasma (10-30ns), resulting in partial thermal decomposition of the pigment causing thermal damage to the surrounding skin.

Recently, with the advancement of technology, picosecond laser systems have entered the field of dermatology, improving the clinical effect of treating pigmented skin diseases. Compared with traditional nanosecond laser systems, picosecond lasers can The higher energy produced in a shorter pulse duration (hundreds of picoseconds) generates high temperature (15,000K) and high pressure (2GPa) through multiphoton ionization in the skin, which is called laser-induced optical breakdown (LIOB). ). LIOB is a nonlinear absorption process that can generate plasma in the skin with an irradiance threshold in the range of 102-104 GW/cm2 or higher (i.e., in the sub-nanosecond range). Therefore, the high temperatures and pressures during LIOB may be accompanied by The plasma expands with audible acoustic signatures and shock wave propagation, leading to cavitation inside the skin. In contrast, the LIOB-related picosecond laser system is more advantageous than existing nanosecond laser systems in that it can be used to treat cavitation through the collective The mechanism (photomechanical and photothermal) achieves the disruption and complete thermal decomposition of the pigment. Therefore, the clinical goal of treating pigmented skin with picosecond laser is to form cavitation uniformly in the epidermis and dermis through laser-induced plasma. , removing the target with minimal thermal damage to surrounding tissue.

For fractionated treatments of the skin, picosecond lasers are often used in conjunction with microlens arrays (MLA) ) can produce multiple micro-beams with minimal thermal damage to surrounding skin tissue compared to a bare beam. However, due to the inherent optical characteristics of uneven beam distribution, MLA usually concentrates the maximum light intensity at the center of the macroscopic beam and reduces the light intensity at both ends. A previous in vitro study showed that MLA-assisted 1064nm picosecond laser at low energy ( ≤2.1mJ/microbeam or radiation exposure = 2.8 J/cm2) setting, vacuoles are unevenly dispersed in the epidermis (100-150μm) through intraepidermal LIOB, but this can hardly treat melanin located deep in the basement membrane (300-500µm). Clinical studies have shown that at H0=1.2J/cm2, laser-induced cavitation is distributed in large quantities in the human epidermis (50-100µm), and the cavitation is only distributed in the epidermis. Holographic beam splitters can also generate microbeams with different patterns for optical imaging. DOE can reduce the energy of incident light and make it uniform. Although there is energy loss, light homogenization can help DOE to distribute microbeams uniformly. More even and constant delivery to the target. The uniformity of the beam distribution depends largely on the focal length of the DOE and the incident wavelength. However, in vitro studies have shown that DOE-assisted picosecond laser treatment can consistently induce small cavitation (~50 μm), but only in the human epidermis. , the insufficient pulse energy of picosecond lasers often hinders the use of DOE for fractionated laser skin treatment of intradermal LIOB.

The purpose of this study was to compare Effects of intradermal LIOB using MLA and DOE on in vitro pigmented porcine skin tissue after 1064 nm picosecond laser high energy irradiation under different treatment conditions. We hypothesized that, under the same conditions, the intrinsic optical mode of MLA would be The DOE can produce more uniform microbeam spatial distribution and laser-induced skin cavitation. Therefore, the significance of this study is to compare the effects of MLA- and DOE-assisted picosecond laser irradiation on skin tissue under high-energy environment. It creates optimal conditions for inducing the formation of small cavitation bubbles of consistent depth in the skin, thereby effectively treating melasma. Ex vivo porcine skin tissue was tested in a high-energy environment using a picosecond laser combined with MLA and DOE to explore the distribution and extent of laser-induced cavitation in the epidermis and dermis. Histological analysis was then performed to quantitatively compare MLA and DOE Skin reactions of LIOB in the dermis.

Materials and Methods

2.1 Light Source

A 1064 nm picosecond Nd:YAG laser system (pulse duration at FWHM = 450 ps; Picore; Bluecore company, Busan, South Korea) was used to induce LIOB in the model and ex vivo porcine skin tissue. The laser system delivered pulse energy up to 1.1 J (1 Hz) to evaluate high-energy settings for potential ablation of deep pigments. A microlens array (MLA focal length = 40 mm, 37 microbeams, diameter = 4 mm, fused silica; Bluecore company, Busan, South Korea) and a diffractive optical element (DOE focal length = 40 mm, 49 microbeams, length = 4 mm, fused silica; Bluecore company, Busan, South Korea) generated multiple microbeams on the target surface for quantitative comparison. To achieve the same energy density on the target surface, four different pulse energy levels of MLA (0.19, 0.38, 0.57, and 0.76 J) and DOE (0.24, 0.48, 0.72, and 0.96 J) were tested. The corresponding microbeam energy (= applied pulse energy/number of microbeams) ranged from 4.9 to 20.5 mJ/microbeam (i.e., 5.1 to 20.5 mJ/microbeam for MLA and 4.9 to 19.6 mJ/microbeam for DOE). The overall spot size was 4 mm for both MLA (circular) and DOE (rectangular). To simulate clinical conditions (e.g., applied energy density and skin texture), laser irradiation results at various energy densities (H0) and focal depths (FD) were tested. Four different H0 (1.5, 3.0, 4.5, and 6.0 J/cm2) and three different FD (0, 5, and 10 mm) were tested to explore the physical effects of treatment conditions on the spatial distribution of microbeams, microbubbles, and laser-induced cavitation in human phantoms and skin tissue. It should be noted that FD refers to the depth of focus in air. Since the mismatch boundary condition is not considered, FD = 0 mm means that the incident microbeam is focused on the target surface, while FD = 10 mm means that the MLA and DOE are close to 10 mm from the surface (i.e., a distance close to 10 mm) and focus the incident microbeam below the target surface. LIOB was confirmed during laser irradiation under all conditions. The two-dimensional (2D) spatial distribution of microbeams from MLA and DOE on the paper surface under various H0 and FD conditions was visualized and characterized using 4 × 4 cm2 black dimming paper. During MLA and DOE irradiation, a picosecond pulse was irradiated on the dimming paper to form LIOB. The irradiated paper surface was then photographed with a digital camera. The size and distribution of laser-induced microbeams on paper were quantified by using Image J (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

2.2 Model experiments

Tissue models were prepared for comparative experiments by using 10% (w/v) porcine gelatin (gel strength 300, type A; Sigma Aldrich, St, Louis, MO, USA) in 70°C distilled water. First, gelatin powder was poured into distilled water and stirred for 25 min. Then, 0.03% w/v melanin (synthetic; Sigma Aldrich, St, Louis, MO, USA) was added to the dissolved mixture as a chromophore. When the melanin was fully melted, the mixture was poured into a 5 cm3 mold and stored at 4°C for 12 h to solidify. The prepared transparent model was used to characterize the 2D spatial distribution of microbeams and the axial distribution of laser-induced microbubbles. To evaluate the LIOB-induced response, single picosecond pulses with MLA and DOE under different conditions were irradiated on the tissue phantoms. The top surface and cross-section of each treated phantom were photographed to identify the spatial distribution of the microbeam spot and explore the axial distribution of laser-induced microbubbles in the phantom. The size and depth of all microbubbles were measured using Image J, and a quantitative comparison between MLA and DOE was performed. The total bubble area inside each macrobeam was measured, and the relationship between the microbubble formation and the applied H0 and beam profile was studied comparatively.

2.3 Ex Vivo Skin Tests

For the in vitro tests, dark miniature pig skin tissue was obtained from CRONEX Crop (Seoul, South Korea) because the scattering rate of pig skin tissue is comparable to that of human skin (1.1 mm-1 for pig dermis and 1.34 mm-1 for human dermis at a wavelength of 1064 nm). MLA and DOE assisted 1064 nm picosecond laser irradiation was performed on skin tissue at energy densities of H0 = 3.0 and 6.0 J/cm2.

After each pulse irradiation, the tissue was moved laterally by 10 µm, with a total treatment length of 200 µm (20 times in total). Overlapping irradiation allowed for distinct spatial distribution of laser-induced cavitation within the skin. Top-view images were captured to measure the spatial distribution of microbeams on the skin surface, allowing for a quantitative comparison between MLA and DOE. After in vitro experiments, all treated tissue samples were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin (Sigma Aldrich, St, Louis, MO, USA) for two days, sectioned into 5 µm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Image J was used to characterize the size and distribution of internal laser-induced cavitation. All tissue sections were photographed using a 100 and 400x optical microscope (Leica DM500, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany). In nonparametric statistical analysis, Mann-Whitney U test was used for comparisons between two and multiple groups, respectively, and p<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

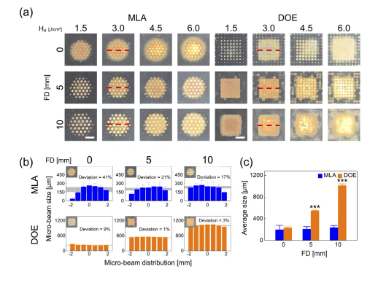

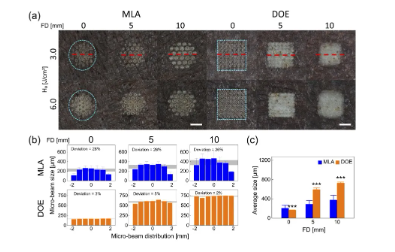

Figure 1 compares the spatial beam profiles of MLA and DOE on black dimming paper under different conditions. According to Figure 1(a), MLA produces a circular profile beam (4 mm in diameter) consisting of 37 microbeams, while DOE produces a rectangular profile beam (4 mm in width) consisting of 49 microbeams. Regardless of FD, both MLA and DOE show that the overall beam spot becomes more blurred with increasing H0. With increasing FD, there is no obvious change in the overall microbeam for MLA, but a significant change in the microbeam size is observed from the overall beam profile. On the other hand, the size of the DOE microbeam increases with increasing FD. However, for all H0, the overall beam size of each DOE microbeam is comparable along the lateral direction. Figure 1(b) shows the lateral distribution of the microbeams irradiated by MLA and DOE at 3.0 J/cm2 (measured from the red dashed line in Figure 1(a)). The deviation of the microbeam size distribution of MLA is relatively large (17~41%) under different FD. The average value of the microbeam size is ~214µm. In contrast, DOE exhibited relatively small deviations (1-9%) in the distribution of microbeam sizes across all FDs. The average DOE microbeam size increased from 229 μm to 1009 μm with increasing FD, indicating a positive correlation with FD. Figure 1(c) shows that the overall MLA microbeam size remained relatively unchanged across all FDs, but the overall DOE microbeam size increased significantly with FD (p<0.001 vs MLA).

Figure 1. Comparison of spatial beam profiles of microlens array (MLA) and diffractive optical element (DOE) at different energy densities (H0, in J/cm2) and depth of focus (FD, in mm):

(a) Top view image of the overall beam spot on black dimming paper, (b) spatial distribution of micro beam size obtained from the center line (red dashed line) of the overall beam (H0=3.0/cm2), and (c) overall micro beam size measured from the overall beam (bar=2mm; ***p<0.001 vs. MLA). The gray area in (b) indicates the measured micro beam size deviation.

Figure 2 shows the ablation response of the tissue simulation model after LIOB generation with MLA and DOE under different conditions. Similar to Figure 1(a), Figure 2(a) demonstrates that MLA and DOE generate beams with circular and rectangular profiles on the model surface, respectively. Both MLA and DOE show that laser-induced microbubbles can be clearly generated on the model surface at FD=0mm. However, as FD increases, the microbubbles on the surface begin to disappear, indicating that the location of the microbubbles is deeper inside the model. Irrespective of FD, the microbubbles produced by MLA and DOE showed more spot areas with increasing H0 due to the increase in the size of individual microbubbles. Figure 2(b) compares the size and distribution of laser-induced microbubbles obtained from the midline of the treated model surface (dashed red line) after irradiation with MLA and DOE at 4.5 J/cm2. MLA produced a non-uniform distribution with a deviation of 33-44%. The largest microbubble size appeared at the center of the MLA overall beam (average microbubble size = ∼291μm), and the overall size of MLA microbubbles was consistent for all FDs. On the other hand, the microbubbles produced by DOE were uniformly distributed with a small deviation of 2∼5%. The average size of DOE microbubbles increased from 190μm to 546μm with increasing FD. It is worth noting that the trend of the microbubbles from MLA and DOE is consistent with the trend of the microbeam spots shown in Figure 1(b). Figure 2(c) shows the relative area (coverage, in %) of microbubbles generated within each overall beam spot as a function of H0 for MLA and DOE at FD=0mm (dashed cyan line in Figure 2(a)). In MLA, the coverage of microbubbles slightly increased with H0 at FD=0mm. In contrast, DOE-induced microbubbles achieved a larger overall beam coverage (up to 40%). The bubble coverage increased linearly with H0 for both groups at FD=0mm (R2=0.92).

Figure 2. Evaluation of the laser-induced response of a gelatin-based skin model (10% gelatin and 0.03% w/v melanin powder) after irradiation with MLA and DOE at different energy densities (H0, in J/cm2) and focal depths (FD, in mm):

(a) Top view (bar=2mm) of the overall beam spot (cyan dashed line) on the model surface, (b) spatial distribution of microbubble size obtained from the center line (red dashed line) of the overall beam spot (H0=4.5/cm2), and (c) comparison of microbubble coverage in each overall beam spot at FD=0mm (R2=0.92).

The gray area in (b) indicates the size deviation of the measured microbubbles.

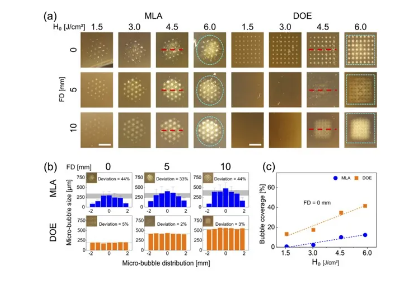

Figure 3. Evaluation of the laser-induced response of the gelatin skin model after irradiation with MLA and DOE at different energy densities (H0, in J/cm2) and focal depths (FD, in mm):

(a) Cross-sectional images of laser-induced microbubbles in the model, (b) axial distribution of microbubbles measured at different focal depths (vertical direction; H0 = 4.5 J/cm2), and (c) quantitative comparison of the overall microbubble depth between MLA and DOE. Note that the cyan dashed line in (a) indicates the end profile of the laser-induced microbubbles in the model (bar = 2 mm).

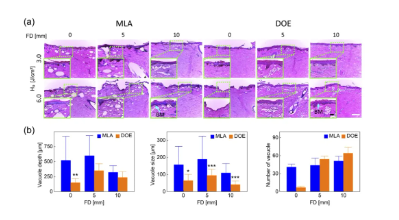

Figure 4 shows the ex vivo pigmented skin after irradiation with MLA and DOE under various conditions. According to Figure 4(a), MLA produces a circular-profile beam spot on the skin surface, while DOE produces a rectangular-profile beam spot, which is consistent with Figures 1(a) and 2(a). In the case of MLA, the microbeam spot becomes blurred with increasing H0 and FD. However, DOE showed no significant changes in microbeams between 3.0 and 6.0 J/cm2, but the microbeam spot size increased with increasing FD. Both groups were associated with superficial thermal damage (whitening) on the tissue surface. Figure 4(b) shows the lateral distribution of MLA and DOE microbeams irradiated at 3.0 J/cm2. MLA had a larger deviation in the microbeam size distribution at all FDs (26∼28%). The average size of MLA microbeams increased from 220μm to 397μm with increasing FD. In contrast, DOE showed a relatively small deviation (2∼5%). The average size of DOE microbeams increased from 165μm to 730μm with increasing FD, indicating a stronger correlation with FD. According to Figure 4(c), the DOE group demonstrated a more significant increase in the overall microbeam size compared to the MLA group, and the overall size was twice that of the MLA group at FD=5 and 10mm (p<0.001 vs. MLA).

Figure 4. Comparison of laser-induced responses of in vitro pigmented pig skin irradiated with MLA and DOE at different energy densities (H0, unit J/cm2) and focal depths (FD, unit mm):

(a) Top view images of the laser-irradiated skin surface, (b) spatial distribution of microbeam size obtained from the center line of the overall spot (red dashed line) (H0=3.0J/cm2), and (c) overall microbeam size measured from the overall spot (H0=3.0 J/cm2). Note that the cyan dashed line in (a) indicates the boundary of the overall spot on the skin surface (bar=2 mm; ***p<0.001 vs. MLA). The gray area in (b) indicates the measured microbeam size deviation.

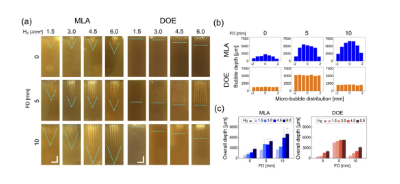

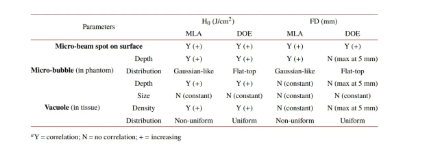

Figure 5 shows H&E staining images of laser-treated skin using MLA and DOE at different FDs under H0=3.0 and 6.0J/cm2. Figure 5(a) shows that laser-induced cavitation was generated under different conditions. At FD=0mm, MLA generated a random group of large cavitations in the epidermis and dermis at 3.0 and 6.0 J/cm2. At FD = 0 and 5 mm, deeper vacuoles with uniform vacuolar size were observed as the epidermis was ablated, but at FD = 10 mm, vacuoles became increasingly shallow and smaller. On the other hand, DOE produced a small number of mild intraepidermal vacuoles and epidermal surface ablation at FD = 0 mm. At FD = 5 and 10 mm, small vacuoles with a relatively high density were evenly distributed under the basement membrane. Figure 5 (b) compares the depth, size, and number of laser-induced vacuoles in the skin under three FDs (H0 = 3.0 J/cm2). MLA had significantly shallower vacuolar depth at FD = 10 mm (321 ± 110 μm), while DOE had the largest vacuolar depth at FD = 5 mm (349 μm at FD = 5 mm, 149 μm at FD = 0 mm, and 236 μm at FD = 10 mm), but it was still shallower than MLA (p < 0.01 at FD = 0 mm). In addition, MLA produced cavitations that were two times larger than DOE (MLA = ∼163 μm, DOE = ∼64 μm; p<0.05 when FD = 0 mm; p<0.001 vs. MLA when FD = 5 and 10 mm). The size of cavitations induced by DOE was consistent and independent of FD. Although the number of cavitations was the lowest, DOE produced significantly more cavitations with increasing FD (FD = 5 and 10 mm). Table 1 summarizes the correlations of laser-induced parameters with H0 and FD between MLA and DOE in the current test. Correlations were determined by a linear increasing trend between each parameter and H0 or FD (e.g., Y(+) when R2 ≥ 0.85).

Figure 5. Histological analysis of dark pig skin after irradiation with different FDs at H0=3.0 and 6.0 J/cm2 by MLA and DOE:

(a) Histological images of laser-irradiated skin tissue (100× and bar=200µm), and (b) quantitative comparison of the depth, size, and number of laser-induced microbubbles in histological images (H0=3.0 J/cm2; *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 vs. MLA). Note that the inlet in (a) (400× and bar = 50 µm) represents the magnified area of the skin surface (light green dashed line), and BM indicates the location of the basement membrane.

Table 1. Correlation of laser-induced parameters with energy density (H0) and focal depth (FD)

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to comparatively evaluate the LIOB effects of MLA and DOE on ex vivo pigmented porcine skin after high-energy 1064 nm picosecond laser irradiation. Since the irradiance of each microbeam ranged from 1.4×103 to 5.4×103 GW/cm2, LIOBs were continuously generated during irradiation regardless of the target. The high energy setting also enabled the deep distribution of microbubbles in the phantom and the laser-induced cavitation in the skin tissue (Figures 3 and 5). However, it is worth noting that the extent of microbubble distribution in the phantom is poorly reflective of the extent of cavitation in the tissue. The optical characteristics of the target material (relatively transparent phantom vs. turbid tissue) can explain the difference in spatial distribution. Preliminary measurements confirmed that DOE loses ~15% of energy due to beam homogenization compared to MLA. Therefore, the applied pulse energy was adjusted to compensate for the energy loss of DOE and provide equivalent output energy and H0 (up to 6.0 J/cm2) during MLA and DOE irradiation. However, due to the difference in the number of microbeams (37 for MLA and 49 for DOE), the microbeam energy of MLA was approximately 10% higher than that of DOE under the same H0 condition. Both the dimming paper and the tissue model confirmed that after the initiation of DOE-assisted LIOB, the uniform distribution of DOE microbeams contributed to the flat-top distribution of microbubbles (Figures 2 and 3). Therefore, multiple DOE microbeams with high energy levels (i.e., up to 20.5 mJ/microbeam) can form deep and denser uniform constant cavitation (size ∼50 μm) in ex vivo porcine skin (depth of 300∼400 μm; Figure 5). It should be noted that the deep and uniform cavitation produced by DOE-assisted irradiation is expected to achieve consistent and predictable ablation of target pigments in the deep dermis. Unlike the MLA group, the cavitation depth in the DOE group was significantly related to FD, because the maximum depth and density of laser-induced cavitation occurred at FD=5 mm (Figure 5). The current findings suggest that DOE may require deeper focusing to maximize laser-induced cavitation under different skin textures. However, additional testing of different FDs is needed to clarify the LIOB effect during DOE-assisted picosecond laser treatment and optimize the final treatment results to achieve continuous cavitation in the deep dermis.

Increasing H0 enables the incident picosecond laser to penetrate deeper into tissues, but it also causes irreversible damage to the skin surface (Figure 4). In particular, MLA-assisted picosecond laser treatment at H0 = 6.0 J/cm2 demonstrated significant surface ablation of the epidermis and dermis (Figures 4 and 5). In addition, higher FD magnified the microbeam spots on the target surface (paper, model, and skin tissue), thereby losing part of the positive effect of the DOE beam. In this study, multiple consecutive laser treatments (20 µm movement, 10 times in total) were performed on the skin using MLA and DOE to produce a series of cavitation bubbles for quantitative comparison and visualization. However, the overlap of multiple microbeams (diameter ∼200 μm) led to the accumulation of thermal damage on the tissue surface (Figure 5 (a)), which amplified the degree of damage (whitening; Figure 4 (a)). Furthermore, unlike previous studies with single treatments at low energies, no significant plasma shielding was observed in the tests at high energy settings, as the cavitation depth increased with increasing H0 for both MLA and DOE (Table 1). As the effects induced by LIOB accumulate in the tissue, multiple treatments could jointly suppress the effects of plasma shielding on cavitation (size and distribution) during irradiation. However, additional single and multiple treatments without beam overlap are required to confirm this finding. Therefore, optimal treatment conditions are required to understand the plasma shielding effect at high energy settings and maintain the current spatial effects of LIOB with MLA and DOE in order to avoid excessive surface ablation or thermal damage. Interestingly, the size of cavitations in both groups remained unchanged (∼160 μm for MLA vs. ∼90 μm for DOE) regardless of changes in H0 and FD. Although DOE was approximately 40% smaller under the same conditions, DOE was more associated with a better distribution (FD = 5 mm), a constant cavitation size (less deviation), and a higher number of cavitations than MLA (Figure 5(b)). The constant microbeam mode of DOE can maintain the equivalent energy of a single microbeam and ultimately produce a large number of consistent intradermal LIOBs in the tissue.

Many previous studies have reported the effects of picosecond laser treatment on ex vivo and human skin tissue. Lee et al. tested 1064nm picosecond laser with MLA (overall spot diameter = 7mm) at H0 = 2.8J/cm2 on ex vivo porcine skin tissue. The study showed that the cavitation bubbles (size 28±10μm) generated by MLA-assisted 1064nm picosecond laser were unevenly dispersed in porcine skin tissue (depth 145±26μm). Although the cavitation bubble size was comparable, its location was much shallower than the current MLA results (size = ∼163μm, depth = ∼350μm at H0 = 3.0 J/cm2). Yeh et al. also tested 1064nm picosecond laser with MLA and produced cavitation (size ∼50μm, located at 50∼100μm) in human skin at H0=1.2 J/cm2. Compared with the MLA results (up to 6.0 J/cm2), the cavitation was smaller and more shallowly distributed in the epidermis. The size difference may be caused by multiple factors, including the optical properties of the skin type (human tissue vs. ex vivo porcine tissue), the microbeam energy level (more than two-fold difference), and the characteristics of the LIOB (number, depth, and size). On the other hand, Tanghetti et al. proposed that 1064nm picosecond laser with DOE induced cavitation of 40μm~60μm in the human epidermis at H0=1.1 J/cm2. Balu et al. also observed laser-induced cavitation in human epidermis of 49 ± 11 μm using multiphoton microscopy after DOE-assisted 1064 nm picosecond laser irradiation at H0 = 0.8 J/cm2 (overall spot diameter = 6 mm). Although the cavitation size was comparable (40 to 60 μm), previous DOE studies limited laser-induced cavitation to the epidermis with low microbeam energy or H0. On the other hand, the present study tested high pulse energy settings (H0 = 1.5 to 6.0 J/cm2) to investigate the dependence of the intradermal LIOB effect in the skin on MLA and DOE and ultimately to evaluate the potential ability to ablate deep melanin. Despite the strong dependence on FD, the DOE group demonstrated high-density laser-induced cavitation of uniform size (∼78 μm) and uniform distribution below the basement membrane (depth 300 to 400 μm). The results of the current study suggest that DOE-assisted picosecond lasers can treat deep skin pigments under high-energy settings. Further testing on human skin should be performed to confirm the findings of this experiment to ensure the clinical effectiveness of dermatologists.

Although DOE-assisted picosecond laser was shown to induce more uniform laser-induced cavitation under the basement membrane, clinical experimental limitations still exist. All targets used in the experiments had relatively flat surfaces to allow for better optical coupling with minimal specular reflection. However, MLA can deposit and use incident laser energy on rough surfaces, while DOE works well on flat surfaces. Therefore, as an important clinical parameter, various surface conditions (e.g., smooth vs. rough) should be examined to validate the current findings of MLA and DOE. Since this study tested pig pigmented skin, ex vivo tissue can hardly reflect in vivo and human tissue conditions in terms of melanin distribution, water content, blood perfusion, and skin temperature. In fact, changes in the optical properties of skin color may alter the threshold and characteristics of LIOB on skin tissue. The lack of skin blood flow makes it difficult to assess bleeding in the superficial epidermis, especially after high-energy laser treatment. Only dark-colored pig skin was used in this study to ensure the initiation of LIOB under all conditions. Therefore, other skin types/colors should be evaluated to clarify the dependence of DOE-induced LIOB on melanin content and distribution. Only three different FDs were chosen to simulate the effect of human skin texture (i.e., surface condition) on the intradermal LIOB response. However, the nonlinear dependence of laser-induced cavitation on FD (Fig. 5) requires testing of various treatment distances to ensure optimal clinical outcomes of DOE-assisted laser treatment. Therefore, for potential clinical translation, further studies are needed to validate the findings in this in vivo porcine model with various skin tones, including the extent of pigment removal, acute and chronic responses to laser treatment of the skin using MLA and DOE, and recurrence rate after pigment treatment.

Conclusion

This study compared the LIOB effect of ex vivo skin tissue under high-energy conditions by using MLA- and DOE-assisted picosecond laser systems. Despite the strong dependence on FD, DOE produced a uniform distribution of microbeam space and resulted in uniform subbasal laser-induced cavitation after intradermal LIOB. Further research will verify the potential effectiveness and safety of DOE-assisted picosecond laser treatment of live pig skin models for clinical conversion.

Original link:

https://opg.optica.org/boe/fulltext.cfm?uri=boe-11-12-7286&id=443954

Foremed Legend

The core founding team of Suzhou Foremed Legend Medical Technology Co., Ltd. comes from well-known universities at home and abroad such as Peking University. Foremed Legend focuses on the design, development and application of high-end medical aesthetic optoelectronic equipment based on compliance and product strength, and is committed to becoming a leading company in the field of high-end medical aesthetic optoelectronic equipment, a provider of integrated diagnosis and treatment intelligent solutions, and a pioneer of medical aesthetic data integration platform.

Through tackling a series of underlying key technologies, Foremed Legend has independently developed a number of high-end medical equipment such as picosecond laser therapy devices, long pulse laser therapy devices, intense pulsed light therapy devices, photoacoustic imaging skin detection devices and cold air therapy devices, and continues to deepen the research and development of core product technologies, using better technical solutions to benefit the vast number of beauty seekers.

Adhering to the principle of science and technology for good, Foremed Legend will work with industry and ecological partners to bring more safe and effective medical aesthetic optoelectronic equipment and integrated diagnosis and treatment solutions to the global medical aesthetic market.

Copyright © Suzhou Foremed Legend Technology Co., Ltd.